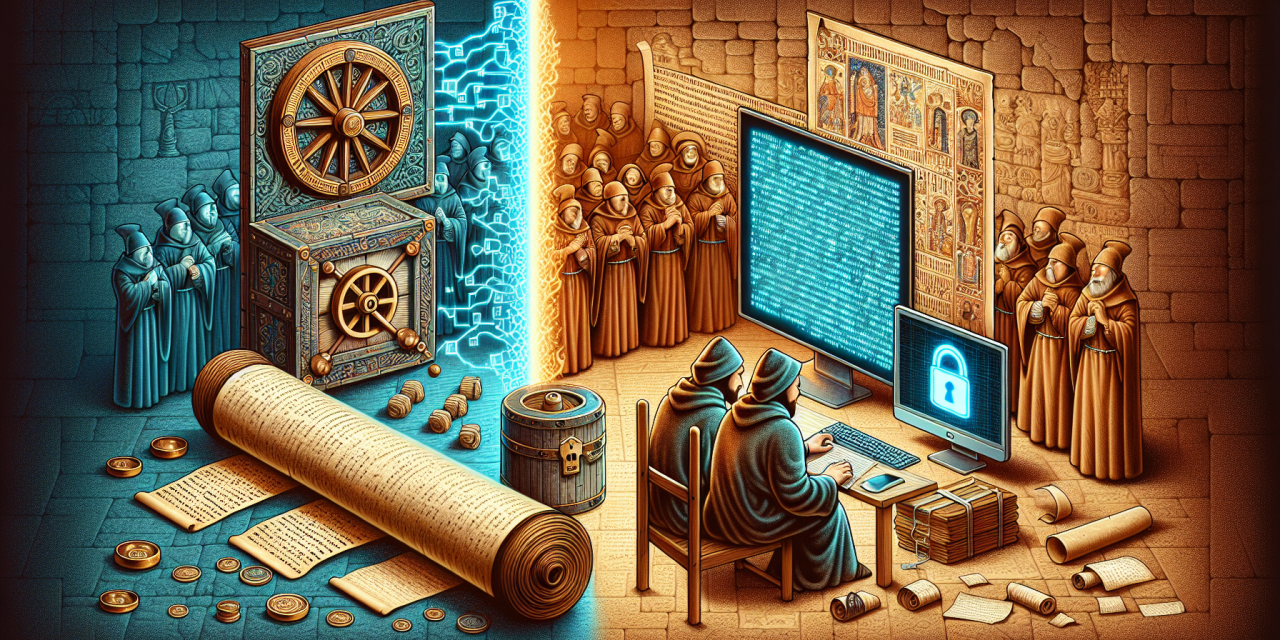

Long before computers existed, humans were already masters of hiding messages in plain sight. Ancient spies, lovers separated by distance, and rebels communicating under oppressive rulers all needed ways to send secret information without getting caught. They developed two brilliant approaches that would later inspire how we protect digital information today: ciphers that scramble messages into secret codes, and steganography that hides messages where nobody thinks to look.

Think of it like this: if your message is a treasure, ciphers are like putting it in a locked box that looks mysterious, while steganography is like hiding it inside something so ordinary that nobody suspects there’s treasure there at all.

Ciphers: When Letters Play Dress-Up

A cipher transforms your original message (called “plaintext”) into a scrambled version (called “ciphertext”) using a set of rules. It’s like having your letters wear costumes to a secret party – they’re still the same letters underneath, but they look completely different.

One of the most famous ancient ciphers belonged to Julius Caesar around 50 BCE. Caesar’s cipher works like a sliding alphabet wheel: you simply shift every letter by the same number of positions. If you shift by 3 positions, A becomes D, B becomes E, C becomes F, and so on. The word “HELLO” would become “KHOOR.” Simple but effective when most people couldn’t read anyway!

Here’s a fun activity you can try: write your name using a Caesar cipher with a shift of 5. Count forward 5 letters for each letter in your name (wrapping around from Z back to A). Your scrambled name would look like gibberish to anyone who doesn’t know the secret number.

Medieval scholars got more creative with substitution ciphers, where each letter consistently replaces another letter, but not in a simple pattern. Imagine if every A in your message became Q, every B became X, every C became F – but following a secret substitution table that only you and your intended recipient knew. Breaking these codes required patience, pattern recognition, and knowledge about which letters appear most frequently in different languages.

Steganography: The Art of Hidden in Plain Sight

While ciphers make messages look obviously secret (even if unreadable), steganography makes secret messages invisible entirely. The word comes from Greek: “steganos” meaning covered or hidden, and “graphia” meaning writing.

Ancient Greeks would write messages on wooden tablets, then cover them with wax and write innocent-looking content on top. The recipient would melt the wax to reveal the hidden message underneath. Roman soldiers tattooed messages on slaves’ shaved heads, waited for hair to grow back, then sent the slaves as messengers to recipients who would shave their heads again to read the secret text.

During World War II, resistance fighters used invisible ink made from lemon juice, milk, or even urine. When heated, these substances would brown and reveal the hidden text. They’d write innocent letters to family members, but between the lines lay crucial military intelligence. The ordinary-looking letter was actually a sophisticated information delivery system.

One particularly clever technique involved modifying existing text. Spies would mark certain letters with tiny pin pricks, or use specific word patterns where every fifth word, when read together, spelled out the real message. Someone reading the surface text would see normal content, but the intended recipient knew to look for the hidden pattern.

Medieval Monks and Their Cryptographic Creativity

Medieval monasteries became unexpected centers of cryptographic innovation. Monks developed complex systems for protecting religious texts and private correspondence. They created cipher wheels, practiced letter substitution using religious symbols, and even embedded secret messages within illuminated manuscripts.

One fascinating technique involved using the first letter of each line in a poem to spell out a hidden message – an acrostic cipher. From the outside, you’d see beautiful religious poetry. But reading downward through the first letters revealed secret communications. Imagine writing a love letter where the first word of each line spells “MEET ME AT SUNSET” while the actual poem discusses gardening!

The Renaissance: When Cryptography Became Science

The Renaissance brought mathematical thinking to secret communication. Polymath Leon Battista Alberti invented the first polyalphabetic cipher around 1467, using multiple alphabet substitutions within a single message. Instead of using the same substitution throughout (like Caesar’s simple shift), Alberti’s system changed the substitution pattern, making patterns much harder to detect.

Think of it like this: if simple substitution is like everyone at a costume party wearing the same type of mask, polyalphabetic ciphers are like people switching between different types of disguises throughout the evening. Much more confusing for anyone trying to figure out who’s who!

Johannes Trithemius wrote the first systematic study of cryptography in 1518, establishing techniques that intelligence agencies would use for centuries. His work showed that protecting information wasn’t just about creativity – it required understanding mathematics, probability, and human psychology.

Why This History Matters for Modern Coders

These ancient techniques reveal fundamental principles that still power modern computer security. Every time you see “https” in a web address, you’re benefiting from mathematical descendants of Caesar’s alphabet shifting. When your messaging app promises end-to-end encryption, it’s using sophisticated versions of substitution ciphers that medieval monks would recognize.

Modern steganography hides messages inside digital images, audio files, or even the unused space in computer files. Your favorite photo could theoretically contain an entire hidden document, with the image looking exactly the same to casual observers. The basic principle remains unchanged from those ancient wax tablets: hide your secret inside something ordinary.

Understanding these historical foundations helps modern coders appreciate why security thinking matters. Those ancient message-hiders faced the same core challenge we face today: how do you share sensitive information across untrusted channels while keeping it away from unwanted eyes? Their solutions teach us that effective security combines mathematical precision with creative thinking about human behavior.

Next time you enter a password or send a private message, remember you’re participating in an ancient human tradition of protecting information. The tools have evolved from lemon juice and wax tablets to quantum-resistant algorithms, but the underlying creative spirit remains remarkably similar. We’re all still trying to keep secrets in a world full of curious minds – we’ve just gotten much more sophisticated about how we do it.