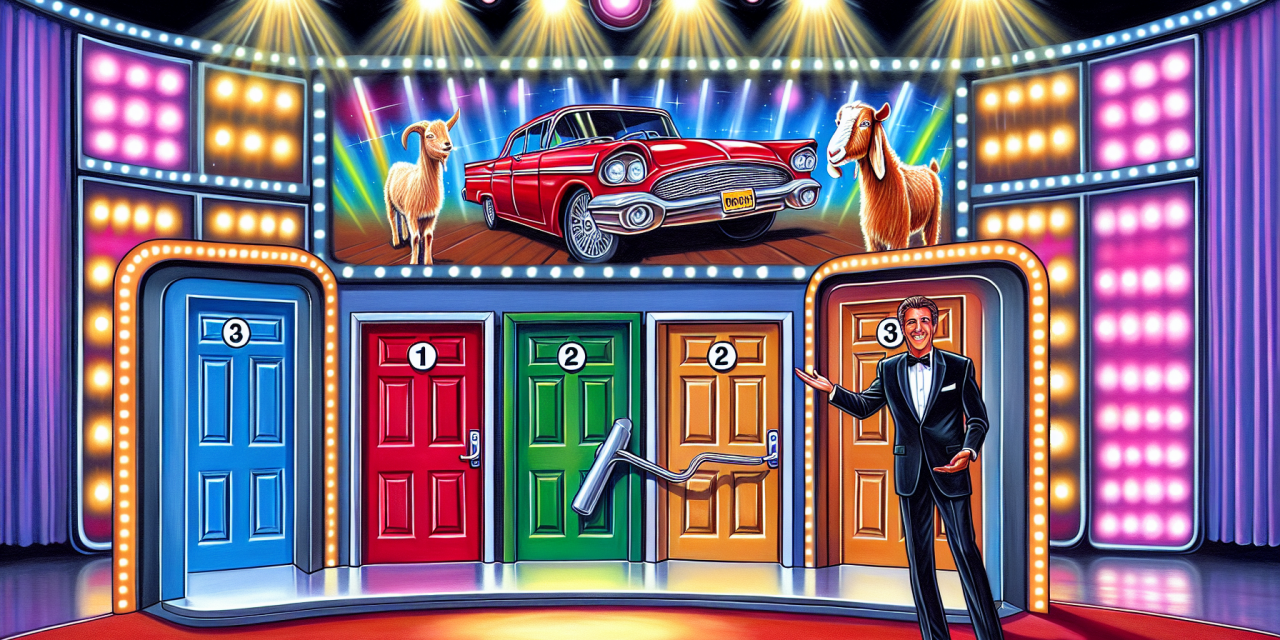

Picture this: You’re standing in front of three doors on a game show. Behind one door is a shiny new car, and behind the other two are goats. You pick door number one. The host, who knows what’s behind each door, opens door number three to reveal a goat. Then comes the question that has stumped mathematicians, confused game show contestants, and sparked heated dinner table debates: “Would you like to switch to door number two?”

Your brain probably screams “It doesn’t matter!” After all, there are two doors left, so it’s got to be 50-50, right? Well, prepare to have your mind twisted like a pretzel, because this famous puzzle—the Monty Hall Problem—reveals something fascinating about how our brains process probability, and more importantly, how the same kind of counterintuitive thinking shows up everywhere in our daily lives.

The Plot Twist That Breaks Brains

Here’s where things get wonderfully weird. You should absolutely switch doors, and here’s why: when you first picked door number one, you had a 1 in 3 chance of being right. That means there was a 2 in 3 chance the car was behind one of the other two doors. When the host opens one of those “other” doors to reveal a goat, that 2 in 3 probability doesn’t just vanish into thin air—it gets concentrated entirely onto the remaining unopened door.

Think of it like this: imagine the game had 100 doors instead of three. You pick one door (1% chance of being right), and the host opens 98 of the remaining doors, all showing goats. Would you stick with your original 1% door, or switch to the one remaining door that now carries the weight of the other 99% probability? When you frame it this way, switching becomes a no-brainer.

This isn’t just mathematical trickery—it’s a perfect example of how our brains, which evolved to make quick decisions about immediate physical threats, sometimes stumble when dealing with abstract probability.

Your Brain’s Probability Blind Spots

Our minds love to find patterns and make quick judgments, but probability doesn’t always play by the rules our brains expect. Just like how optical illusions trick our visual processing, probability problems can create “statistical illusions” that feel completely wrong even when they’re mathematically correct.

The Monty Hall Problem taps into several mental shortcuts that usually serve us well but occasionally lead us astray. We tend to think that past events affect future outcomes (like believing a coin is “due” for heads after several tails), and we often treat uncertainty as if all possibilities are equally likely just because we don’t know the answer.

But here’s the beautiful part: once you understand why your intuition misfires on the Monty Hall Problem, you start noticing similar patterns everywhere. It’s like getting a new pair of glasses that suddenly makes hidden probability puzzles come into focus all around you.

Hidden Monty Hall Moments in Real Life

Ever wondered why your other checkout line always seems to move faster? Or why you always seem to catch more red lights when you’re running late? These everyday frustrations often involve the same counterintuitive probability thinking as the Monty Hall Problem.

Consider medical testing. If a test for a rare disease is 99% accurate and you test positive, your brain might think “Oh no, I probably have this disease!” But just like the door problem, the initial probability matters enormously. If the disease affects only 1 in 1,000 people, then even with a positive test result on a 99% accurate test, there’s still a good chance you’re healthy. The math isn’t intuitive, but it’s crucial for making informed decisions.

Or think about job interviews. You might assume that if you’ve been called back for a second interview, your chances are 50-50 since there are two candidates left. But that’s door-thinking again! Your initial probability depends on how many people applied originally and what information the interviewer gained by eliminating others.

The Internet’s Probability Playground

Social media algorithms create fascinating Monty Hall-style situations every day. When your friend posts about their amazing vacation, you’re not seeing the 98 boring posts they didn’t share—you’re seeing the curated highlight reel. Your brain treats this like the final two doors: “Either my life is as exciting as theirs, or it isn’t,” when the real probability calculation should factor in all the unshared moments.

Search engines work similarly. When you Google symptoms and find scary diagnoses, you’re essentially looking at the doors the internet “host” has chosen to show you. The algorithm reveals the most clicked-on, most dramatic “doors,” while quietly keeping the mundane, reassuring explanations closed.

Training Your Probability Intuition

The good news is that you can actually rewire your brain’s probability processing, just like building any other skill. Start by playing around with the original Monty Hall Problem using online simulators—actually run the experiment hundreds of times and watch the switching strategy win roughly twice as often as staying put.

Practice spotting “base rate” information in daily life. When you hear news about a plane crash, your brain focuses on the dramatic event, but a probability-trained mind automatically asks: “Out of how many flights today?” The crash becomes much less personally relevant when you realize millions of flights happen safely.

Challenge yourself to think beyond the immediate options. When facing any either/or decision, ask yourself: “What information was available before these became the final two choices?” Just like the game show, the history of eliminated options carries important probability clues.

Embracing Beautiful Uncertainty

Here’s perhaps the most liberating insight from the Monty Hall Problem: being wrong about probability doesn’t make you stupid—it makes you human. Even brilliant mathematicians initially rejected the correct solution when this problem first gained fame. Our brains evolved for a world where quick pattern recognition kept us alive, not for calculating conditional probabilities.

But understanding these blind spots gives us a superpower. We can step back from our gut reactions and ask better questions. We can make more thoughtful decisions about everything from career moves to health choices to investment strategies.

The next time you find yourself facing what seems like a simple 50-50 choice, pause and think like that game show contestant. What doors have already been opened? What information shaped how you got to these final options? Sometimes, just like in the famous problem, the counterintuitive move turns out to be the smartest choice of all.

After all, in a world full of hidden doors and concealed information, the most valuable skill isn’t always trusting your first instinct—sometimes it’s knowing when to switch.