Picture this: It’s April 1970, and you’re floating 200,000 miles from Earth in a damaged spacecraft. Your coffee maker breaks, your toaster stops working, and oh yes—your life support system just exploded.

What do you do?

If you’re the crew of Apollo 13, you reach for the cosmic equivalent of duct tape and get creative.

[youtube]Tid44iy6Rjs[/youtube]

The real Apollo 13 crisis didn’t actually involve duct tape (though plenty of later missions did), but it perfectly captures something we need more of in today’s world: the MacGyver mindset.

This is the ability to look at a problem, glance around at what you’ve got, and figure out how to MacGyver your way to a solution. This kind of thinking isn’t just for astronauts—it’s exactly the mindset that makes great coders, engineers, and problem-solvers of all kinds.

When Plans Meet Reality (Spoiler: Plans Lose)

Here’s the thing about space missions: they’re basically the ultimate coding project. You spend years planning every detail, writing procedures for everything you can imagine, and testing your systems until they’re bulletproof.

Then you launch, and reality says, “Hold my space juice.”

On Apollo 13, an oxygen tank exploded, knocking out power and life support. The crew had to move into the lunar module—which was designed to keep two people alive for two days, not three people for four days.

Think of it like trying to run a video game designed for your phone on a calculator. Technically possible, but you’re going to need to get creative with your resource management.

The ground team and astronauts had to become the ultimate debugging crew. They couldn’t just restart the program or download a patch. They had to look at what was actually working, figure out what they absolutely needed, and find ways to make limited resources stretch further than anyone thought possible.

The Art of “What Have We Got?”

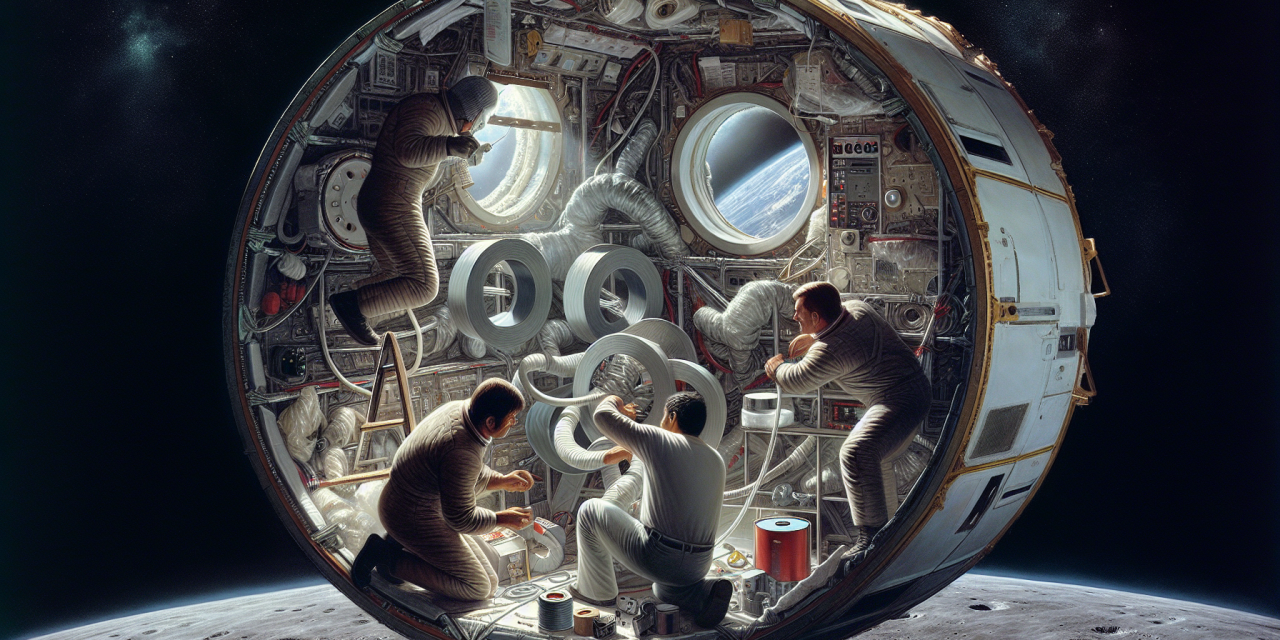

One of the most famous MacGyver moments happened with the carbon dioxide scrubbers. The command module’s square filters couldn’t fit in the lunar module’s round receptacles.

As one NASA engineer put it, they had to figure out how to fit a square peg in a round hole—literally.

The solution?

The ground team dumped out a box containing everything available to the astronauts: plastic bags, cardboard, tape, hoses from their space suits, even the cover of their flight manual. They had to build a working air filter using only these items, then talk the astronauts through building the same thing in space.

[youtube]KHQhp2cGZtE[/youtube]

This is exactly how great programmers think when they encounter a bug at 2 AM and the usual solutions aren’t working. You don’t give up—you inventory what you have, think creatively about how those pieces might fit together, and sometimes discover solutions that work better than your original plan.

Duct Tape: The Universal Programming Language

While Apollo 13 famously used plastic bags and cardboard, later missions absolutely relied on what NASA called “gray tape”—which was basically space-grade duct tape.

Apollo 17 astronauts used it to repair a damaged moon buggy fender. Without that fix, moon dust would have covered their equipment and potentially ruined their mission.

But here’s what’s beautiful about duct tape thinking: it’s not about the tape itself.

It’s about approaching problems with the assumption that there’s probably a solution hiding in plain sight, even if it’s not the “official” one you were taught.

In programming, we call this “hacking” in the original sense—cleverly working around limitations to get things done.

Maybe:

- Your code needs to handle a file format it wasn’t designed for, so you find a creative way to convert the data first

- Your algorithm is too slow, so you cache results or find a shortcut that gets you 90% of the way there in one-tenth the time

The MacGyver Mindset in Your Backpack

You don’t need to be hurtling through space to practice this kind of thinking. Every time you’re working on a project—coding or otherwise—and hit a wall, you have a choice.

You can:

- Wait for someone to provide the “right” solution, OR

- Channel your inner Apollo engineer and ask, “What do I actually have available, and how might I use it differently?”

Practical examples:

- Building a website but don’t have access to a fancy database? Store your data in a simple text file instead

- Coding a game but don’t know how to make professional sprites? Start with simple shapes and focus on making the gameplay amazing first

The most elegant code often comes from these constraint-driven moments. When you can’t brute-force your way through a problem with unlimited resources, you’re forced to think more carefully about what you actually need and find the most efficient path there.

Failure as Your Flight Director

Gene Kranz, the flight director during Apollo 13, had a famous motto: “Failure is not an option.” But here’s what he actually meant: when things go wrong, you don’t have the luxury of giving up.

You inventory your resources, you get creative, and you find a way forward.

This attitude transforms how you approach problems:

- Instead of seeing limitations as roadblocks → see them as design constraints that force creative thinking

- Instead of seeing failures as endings → see them as data points that help you understand what doesn’t work

Every great coder has stories about the time their “duct tape solution” saved the day. Maybe it was a quick script that processed data in a completely unconventional way, or a clever workaround that bought time while they developed a more permanent fix.

Building Your Own Ground Control

The Apollo teams succeeded because they combined deep technical knowledge with creative problem-solving and collaborative thinking.

When you’re stuck on a problem, try channeling that same approach:

First: Step back and clearly define what you actually need to accomplish. Like the Apollo 13 crew, separate the “nice-to-haves” from the “need-to-survives.” What’s the core problem you’re trying to solve?

Second: Inventory your resources honestly. What tools, knowledge, and materials do you actually have access to? Sometimes the solution involves using something in a way it wasn’t originally intended—and that’s perfectly okay.

Third: Don’t be afraid to think unconventionally. The most creative solutions often come from combining ideas from completely different domains. Maybe a technique from music helps you understand data patterns, or a concept from cooking helps you think about timing in your code.

[link]https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/missions/apollo13.html[/link]

The Creative Spark Lives On

The next time you’re facing a problem that seems impossible, remember those engineers in Houston dumping out a box of random spacecraft parts, determined to find a way to keep three astronauts alive with nothing but ingenuity and gray tape.

That same creative spark lives in every problem you’ll ever encounter—you just need to give it space to breathe.

Ready to develop your own MacGyver mindset? Start by looking at your current coding challenges not as obstacles, but as opportunities to get creative with the tools you already have.