Picture this: You’re watching Jurassic Park for the first time, heart pounding as the T-Rex crashes through the jungle. That massive head swinging toward the camera, those teeth gleaming in the rain, the earth-shaking footsteps—it feels absolutely real. What might surprise you is that some of the most convincing dinosaurs in cinema history weren’t created with cutting-edge computer graphics at all. They were built by hand, operated by teams of people, and moved in ways that would make a master puppeteer weep with joy.

The story of Jurassic Park’s creatures isn’t just about movie magic—it’s a brilliant example of how technical limitations can spark the most creative solutions. Just like a coder facing memory constraints who discovers a more elegant algorithm, the film’s creators turned their biggest challenges into their greatest strengths.

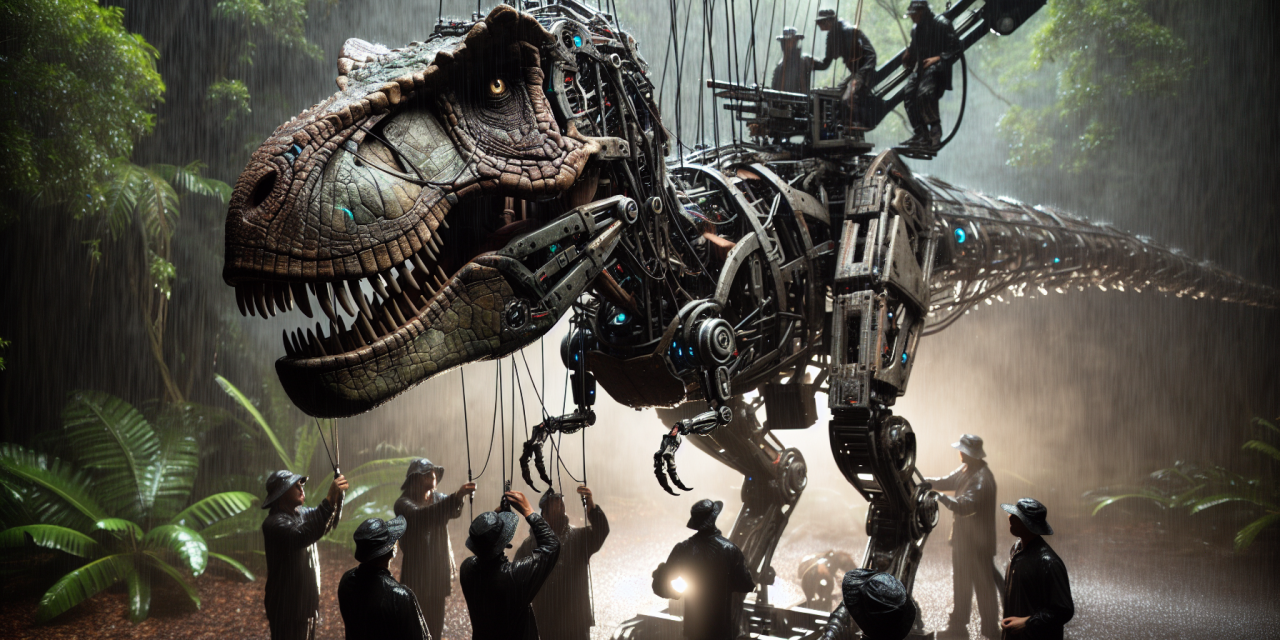

See how the VFX team blended animatronics and CGI to create Jurassic Park’s iconic dinosaurs.

When Technology Hits a Wall

Back in 1993, computer-generated imagery was like having a sports car with a lawnmower engine—impressive in theory, but painfully slow in practice. Creating just one frame of a realistic dinosaur could take a computer hours or even days to render. Imagine trying to animate an entire action sequence when each second requires 24 frames, and each frame takes your computer half a day to create. You’d be waiting months just to see if your dinosaur blinked convincingly.

The Jurassic Park team faced exactly this problem. They needed close-up shots of dinosaurs interacting with actors, reacting to sounds, even breathing naturally. CGI could handle the sweeping aerial shots and some of the running sequences, but for the intimate moments—when you needed to see every wrinkle of skin, every twitch of an eye—the computers of the early ’90s simply weren’t fast enough or sophisticated enough to deliver.

It’s like trying to paint a detailed portrait with a brush the size of a broom. Technically possible, but probably not the best tool for the job.

The Puppet Masters Step In

Enter Stan Winston’s animatronics team, armed with steel skeletons, hydraulic muscles, and an almost supernatural understanding of how creatures move. These weren’t your average hand puppets—they were sophisticated mechanical beings that weighed thousands of pounds and required entire crews to operate.

Think of an animatronic dinosaur as the ultimate collaborative robot. Unlike a computer program running on a single machine, each creature was controlled by multiple puppeteers working in perfect harmony. One person might control the head movements, another the eye blinks, a third the breathing, and several more the body positioning. It was like conducting an orchestra where every musician controlled a different part of the same massive instrument.

The T-Rex head alone required over a dozen operators. They practiced for weeks to coordinate their movements, learning to breathe life into tons of metal and rubber. When you watch that famous scene where the T-Rex peers into the overturned tour vehicle, you’re actually watching the synchronized performance of an entire team, each person responsible for making their small part feel completely alive.

The Beauty of Hybrid Solutions

Here’s where the Jurassic Park team showed the kind of problem-solving brilliance that makes any coder’s heart sing: instead of seeing CGI and animatronics as competing technologies, they treated them like complementary tools in a well-organized toolbox. Each technology handled what it did best.

CGI excelled at wide shots, fast movements, and physically impossible actions—like a Gallimimus herd stampeding across an open plain. The computers could calculate the physics of dozens of running dinosaurs without breaking a sweat. But for the close-ups, the subtle expressions, the moments where an actor needed to touch or interact with a creature, animatronics reigned supreme.

It’s like choosing between a calculator and an abacus. Neither is inherently better—each has situations where it’s the perfect tool. A wise problem-solver uses both when appropriate, rather than forcing one to do a job it’s not suited for.

When Constraints Spark Innovation

The fascinating thing about the Jurassic Park approach is how the technical limitations actually improved the final result. Because animatronic creatures were so expensive and time-consuming to build and operate, the filmmakers had to be incredibly thoughtful about when and how to use them. Every shot had to count.

This constraint forced them to think like master storytellers. Instead of showing dinosaurs constantly, they learned the power of strategic revelation. That T-Rex scene works partly because you don’t see the full creature until the perfect dramatic moment. The buildup—footsteps in the water, the vibrating glass, the distant roar—makes the eventual reveal even more impactful.

Programmers know this principle well. When you’re working with limited memory or processing power, you can’t afford to waste resources. This constraint often leads to more elegant, efficient code. The limitations force you to find the essential core of what you’re trying to achieve and strip away everything unnecessary.

The Teamwork Revolution

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the animatronics approach was how it transformed filmmaking from a solitary craft into a collaborative art form. Creating a believable dinosaur suddenly required expertise from engineers, artists, animal behaviorists, computer programmers, mechanical specialists, and performers—all working in perfect coordination.

Each animatronic creature was essentially a complex system requiring different types of intelligence to function. The mechanical engineers ensured the skeleton could support the weight and movement. The artists crafted the skin textures and color patterns. The programmers wrote control systems to translate human input into creature movement. The performers studied real animals to understand natural motion patterns.

This collaborative approach mirrors how modern software development works. No single person writes today’s complex applications alone. Instead, teams of specialists—front-end developers, back-end engineers, database experts, user experience designers, security specialists—contribute their unique skills to create something none of them could build solo.

The Lasting Impact

Today’s film industry has computer graphics technology that would seem like science fiction to the Jurassic Park team. Modern computers can render photorealistic creatures in real-time, and digital dinosaurs can do things that would be physically impossible for animatronic puppets.

Yet many filmmakers still choose to include practical effects in their movies. They’ve learned that audiences can somehow sense the difference between something that physically exists and something created entirely in computers. There’s a weight, a presence, an authenticity to objects that actually interact with light and shadow, that push air around when they move, that actors can genuinely react to because they’re really there.

The Jurassic Park lesson echoes through every field where technology meets creativity. Sometimes the most advanced tool isn’t the best tool for every job. Sometimes constraints force you to discover solutions you never would have found if you’d had unlimited resources. And sometimes the magic happens not in spite of limitations, but because of them.

The next time you face a technical challenge that seems impossibly difficult with your available tools, remember those puppeteers crouched beneath a giant T-Rex head, working in perfect synchronization to bring a extinct creature back to life. They couldn’t do everything, so they did what they could do extraordinarily well—and changed cinema forever in the process.